(Un)Real Life. Nicolas Dewavrin.

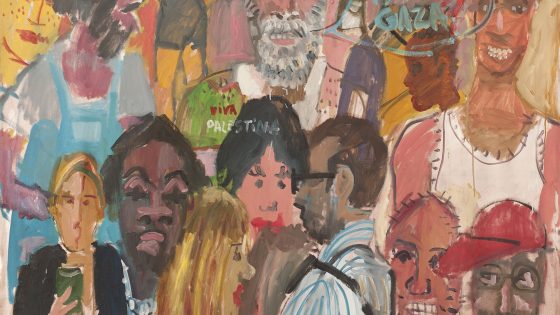

Artists: Gioele Amaro, Saelia Aparicio, Thibault-Théodore Babin, Robert Brambora, Amy Brener, Antoine Carbonne, Justin Fidzpatrick, Rubén Fuentes, Cecilia Granara, Lewis Hammond, Motoko Ishibashi, Oda Jaune, Emily Ludwig Shaffer, Théo Mercier, Rasmus Myrup, Marguerite Piard, Lorena Prain, Paloma Proudfoot, Romain Sarrot y Tyler Thacker.

Surprise!

In the conclusion of his seminal book, History of Surrealism, Maurice Nadeau describes the surrealist movement as a failure: “the ways of thinking and behaving on which [the surrealists] wanted to act electively were in no way transformed by their action. “(Nadeau, 1964, 180) The surrealist movement bore, at its heart, an espoir fou (a ‘crazy hope’, ‘fou’ is a reference to André Breton’s idea of l’amour fou): that of revolutionizing humanity and the world by stimulating a new way of thinking, one that would be highly personal and freed from the dictature of reason. The explorations of the unconscious aimed at liberating society from its alienating structures by cultivating a form of pure thought, preserved from the vicissitudes of the violent world in which the surrealists evolved. The movement’s ideals could thus be equated to a true political program, alike other avant-garde movements, which invested art with the power to transform reality.

It was an inevitable failure. But this unreasonable ambition is also the reason for the persistence of the influence of surrealism on contemporary art. Because despite the impossibility of changing the intimate structure of the world, the movement was a bubbling research laboratory. It developed many methods for stimulating liberated thinking, all of which had at least one point in common: they all created a feeling of wonder and surprise when discovering the results to which they led.

And this is not innocent. The Belgian philosopher Catherine Malabou, basing herself on the research of the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, defines the condition of the contemporary subject as an inability to wonder. (Malabou,

2013, 11) Wonder is positioned by Malabou as the origin of philosophical thought, since it allows the subject to be present to itself. When faced with a surprising object, the subject wonders: what is it that surprises me? Is it the object of surprise or my own ability to wonder? It is this moment of questioning that pushes the subject to reconsider the real and their relationship to the world. (Malabou, 2013, 9) Wonder is therefore positioned as the fundamental condition of philosophical thinking.

In this sense we could say that the battle of the surrealist movement was in fact the battle of wonder. The tactics developed by the surrealists aimed at triggering wonder in order to push the spectator to reimagine its social, political, and psychological conditions. The artists of (Un)real Life are thus linked to the movement more by a shared ethics of wonder than by a direct aesthetic or thematic reference (although present in some works).

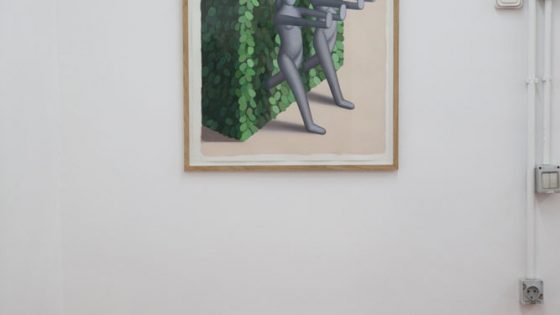

Wonder first arises from a formal transformation of the real. As Ann Coxon, curator at Tate Modern says in an article on the painter Dorothea Tanning, there are three mechanisms through which a work can enter into the surreal: either by a transformation of scale, form or function. (Coxon, 2019) In Antoine Carbonne’s work for example, we see the three of them: a transformation of scale with mountains becoming only heaps of sand when compared to the large columns on the left; transformation of form with the introduction of a seaside landscape at the heart of one of these peaks; and finally a transformation of function with the palm-treeturned- palace. In Justin Fitzpatrick’s there are two: transformation of scale and shape since the main dish seems to have mutated into a new kind of super-insect served on a bed of lettuce and radishes, while the waiter is miniaturized.

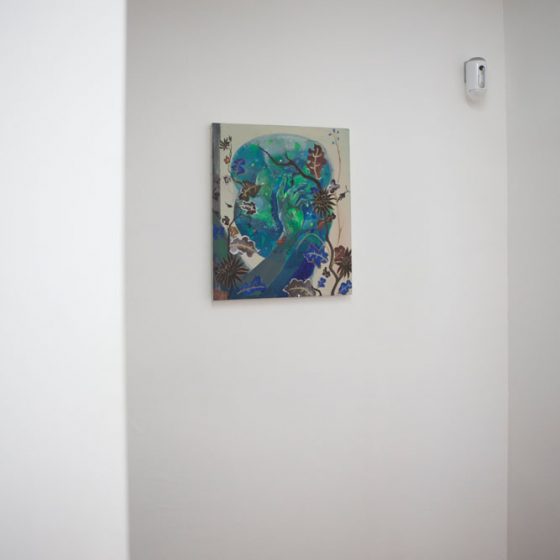

Wonder also comes from a manipulation of the mediums that the artists of (Un)real Life work with. Oda Jaune, for example, designed a series of paintings that, when turned upside down, reveal a new meaning. Robert Brambora’s aggressive dogs are caught in a canvas that takes the form of a languid kiss, creating a radical opposition between form and substance. Marguerite Piard meanwhile uses stones as her medium. Adapting to the shape of the minerals, the faces she paints, however peaceful, find themselves crushed, thereby creating a sense of cheerful ridicule. Amy Brener, on the other hand, challenges traditional genres by proposing a futuristic work at the crossroads of tapestry, sculpture, and clothing. Amaro Gioele, finally. He manipulates our expectations by proposing two works that at first glance look exactly like a painting but that are in fact entirely digital creations.

Wonder finally arises through the act of association. In line with the surrealist philosophy of free association, the sculptors of (Un)real Life twist materials and objects to reveal new, hybrid forms that defy reason. One thinks of Aparicio Saelia’s mutant and sexualized shoe, of the various objects gleaned and encapsulated by Amy Brener, and of the sensual associations of Paloma Proudfoot. Together they offer a new reading of the world and point to new ways of being-in-the-world and experiencing reality.

Wonder can therefore be a useful prism to analyse the lasting influence of surrealism in contemporary art. More than the movement’s themes or aesthetics, it is perhaps its beliefs and tactics that resisted to the passage of time, constantly reinventing themselves to adapt to contemporary social, political and artistic conditions.

Wonder can therefore be a useful tool to analyse the influence of surrealism in contemporary art beyond its themes and aesthetics, and for updating the critique of rationality. More generally, it would be interesting to interrogate the essential role of wonder in the process of presenting and receiving art. Because if art claims to foster new ways of thinking, its exhibition too should be inseparable from an experience of wonder. Institutions and curators should thus think about how to introduce it into their practices, and how to remain malleable enough to evolve in response to it.

Text by Camille Bréchignac

Works cited

Coxon, Ann. Dorothea Tanning, Tate Modern. Selvedge, Issue 87, p.89, 2019.

Johnston, Adrian, and Catherine Malabou. Self and Emotional Life: Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Neuroscience. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Nadeau, Maurice. Histoire du Surréalisme. Éditions du Seuil, Paris, 1964.

Organizes: